No products in the cart.

Berlin 1948/49: The airlift to end all wars – and launch an industry

“Rugged,” said one airman of the rest of the crew involved in the largest air rescue operation in history. “Rugged as a sunovabitch.”

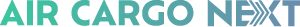

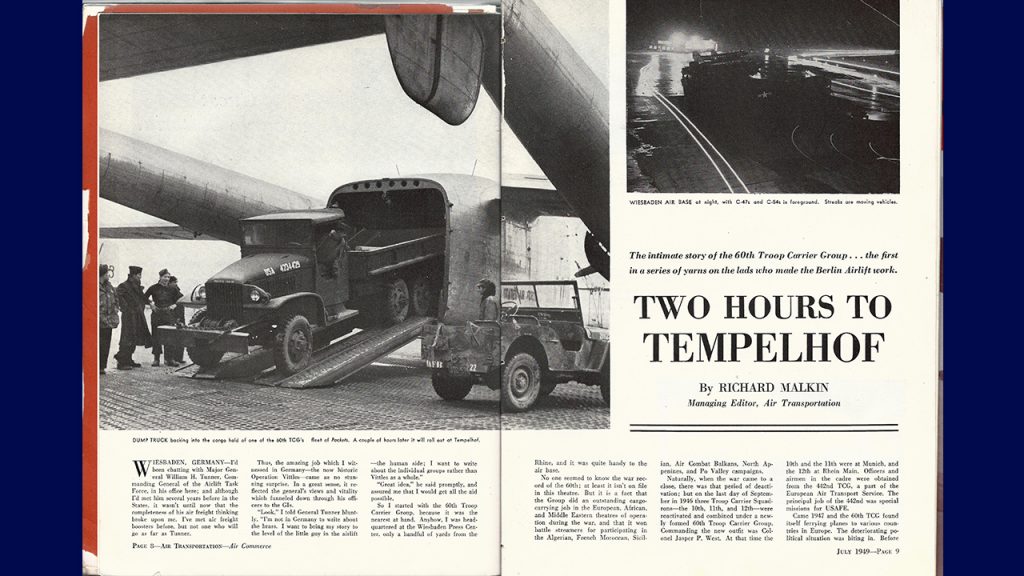

These were the words relayed to American air cargo professionals in the seminal 1949 series of articles penned by Richard Malkin, the legendary original managing editor of Air Transportation magazine, which decades later became Air Cargo World. Malkin spent weeks with the 60th Troop Carrier Group, which helped keep thousands of West Berliners alive in the early days of the Cold War. In the July 1949 issue, the first of these articles ran, called “Two Hours to Tempelhof” (see above) and it remains one of the most exciting and enjoyable reads ever published in this periodical.

Speaking with Maj. Gen. William H. Turner in Wiesbaden, Germany, Malkin said he didn’t want to write about the “brass” in charge of the operation but the everyday G.I.s, “the little guy in the airlift – the human side.” The general obliged, giving Malkin free rein to chat up the men.

Speaking with Maj. Gen. William H. Turner in Wiesbaden, Germany, Malkin said he didn’t want to write about the “brass” in charge of the operation but the everyday G.I.s, “the little guy in the airlift – the human side.” The general obliged, giving Malkin free rein to chat up the men.

The 60th Troop Carrier Group had served admirably – if a bit anonymously – flying supplies to the troops fighting in Africa, Europe and the Middle East during World War II. In 1945, the 60th was deactivated briefly but was reformed in the fall of 1946, commanded by Col. Jasper P. West. From 1947 to 1948, the group ferried aircraft and troops to various locations in Europe and the Middle East during the violent birth of the Jewish state of Israel.

As the Cold War began to congeal over who would control the divided city of Berlin, the 60th crews became some of the most active flyers in the European Theater, bringing supplies to the citizens of West Berlin via one of three narrow air corridors over Soviet-held territory in Eastern Germany. When the Soviet blockade of all road, rail and river access to the city began at the end of June 1948, the U.S. Air Force launched what was called “Operation Vittles,” which would last for more than a year, and was joined by similar round-the-clock operations by air forces in the British and French Occupation Zones.

The toll the work took on the crews, as well as the “war weary” aircraft was brutal, Malkin described. From the airfields at Rhein-Main and Wiesbaden air bases, the 60th crews worked 18-hour days, with average monthly flying times of 196 and 197 hours during July and August. Turnaround times at Wiesbaden and Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport were typically two to three minutes, he wrote.

“Medical authorities will tell you that four hours’ flying time is equivalent to eight hours’ labor on the ground,” Malkin added. When asked if the task was a “hot job,” one of the crewmen responded, “Say, mister, in the first month alone we consumed a full year’s supply of gasoline and parts.”

The majority of aircraft used in the Airlift were the 3.5-tonne capacity C-47 “Gooney Birds,” the military version of the workhorse DC-3, and the larger 10-tonne capacity C-54s, the military version of the four-engined DC-4. Later, the ungainly C-119 “Flying Boxcars” were also added to the constant stream of aircraft flowing into Tempelhof.

But those incremental tonnes slowly added up. Nearly 300,000 flights were made, nonstop, during Operation Vittles, delivering about 2.3 million tonnes of cargo that kept nearly 2 million people in the German capital alive and functioning. At first, the flights averaged 5,000 tonnes of supplies per day, but by the end of the mission, the “air bridge” was averaging 8,000 tonnes daily – proving that the novelty of cargo delivery by air could become a serious business.

The awed Soviets knew they were beaten by the spring of 1949, and they lifted the blockade in May, but Vittles continued until September, to build up a stockpile in case the Russians reneged.

“It is a tribute to the men of that Group that, during this difficult time, not a single mission to which they had been assigned remained unfulfilled,” Malkin summed up. “Blood, sweat and tears? Add guts and perseverance to that!”