No products in the cart.

75th Anniversary Snapshot: Redefining fast – the evolution of express

For most of the early decades of Air Transportation magazine, the venerable periodical that eventually became Air Cargo World, the articles were about ever-larger, ever-faster aircraft that were capable of hauling enormous loads across the planet. While speed was always a selling point, much of the industry was trying to prove that it could compete with transporting large objects often handled by road, ocean and rail modes.

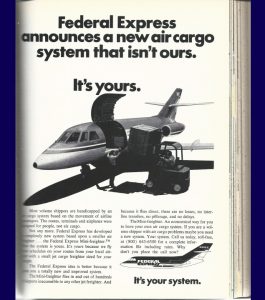

Then, sometime in 1972, after the magazine’s name was briefly changed to Cargo AirLift, readers began to see a few curious looking ads with smaller jets, painted a distinctive purple and orange. The cargo they carried were mostly small packages and letters, but it was the remarkable delivery time that caught readers’ attention.

It was Fred Smith’s Federal Express, of course (at left), as it was about to revolutionize the industry by becoming an integrator and promising overnight delivery anywhere in the United States, based on the shipper’s need, not on the schedule of a passenger jet. One of those original Dassault Falcon 20 jets became so famous it is now parked in the Smithsonian Institute’s Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

It was Fred Smith’s Federal Express, of course (at left), as it was about to revolutionize the industry by becoming an integrator and promising overnight delivery anywhere in the United States, based on the shipper’s need, not on the schedule of a passenger jet. One of those original Dassault Falcon 20 jets became so famous it is now parked in the Smithsonian Institute’s Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

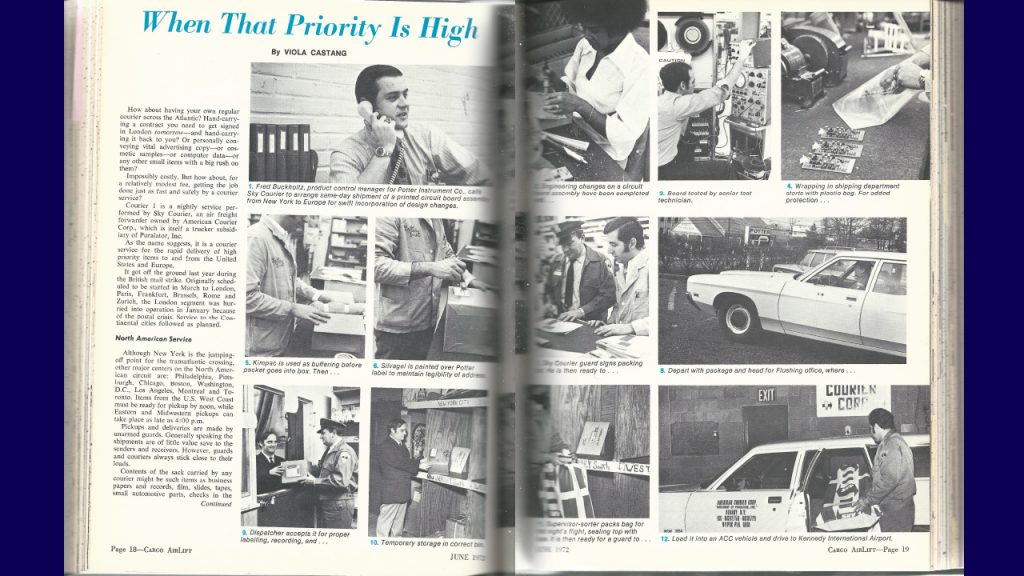

By June of that year, the magazine ran a photo essay, “When That Priority Is High,” depicting the next logical step in the overnight races – trans-continental travel.

“How about having your own regular courier across the Atlantic? Hand-carrying a contract you need to get signed in London tomorrow – and hand-carrying it back to you?” the article began. The photos then described the journey of a trans-Atlantic package carried by Courier 1, a nightly service that had been launched the year before by freight forwarder Sky Courier, owned by a subsidiary of Puralator, Inc.

The photos start (below) with an official from the Potter Instrument Co., in New York, phoning Sky Courier to arrange the delivery of a printed circuit board to Europe as part of a last-minute design change, and continue on, depicted technicians testing the redesigned board, wrapping it in plastic, then in cellulose-based Kimpac for extra cushioning, before handing it to a road courier who drives it to the dispatcher’s office in Flushing, N.Y. There it is stored briefly until it is picked up again and driven to JFK Airport, accompanied by a uniformed guard.

In total, it was a 12-step process that is today cut down to about three steps. But in 1972, it seemed as exotic as an Apollo space mission, yet only cost a modest rush charge.

In total, it was a 12-step process that is today cut down to about three steps. But in 1972, it seemed as exotic as an Apollo space mission, yet only cost a modest rush charge.

Fast-forward 22 years to the January 1994 issue of Air Cargo World, and we see the beginnings of the next logical step in express shipping: same-day air. The internet was still a relative novelty, and Amazon would not be founded for another six months, but several carriers in early 1994 were already providing service for this growing need for same-day delivery – including Delta’s Dash and USAir’s PDQ programs – from airport to airport.

What next advancement in speed will we see in 20 more years? A rise in drone last-mile delivery? Maybe a commercial hyperloop will disrupt the concept of surface transport. Perhaps we’ll eliminate delivery altogether, with much more advanced 3D printing technology that will empower customers to download and create new goods in their homes and businesses.

We may soon be approaching the event horizon of instant gratification in a few more years, but until then, we’ll just have to be patient with the nearly 70-year-old technology of subsonic jet travel.